Deep Learning and the Demand for Interpretability

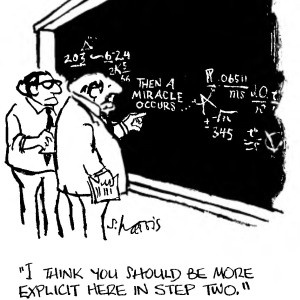

Deep learning has always been under fire for a lot of things in a lot of contexts. There is criticism about the arbitrariness of its hyperparameters and choice of architecture (Yann LeCun’s strong reaction to a rejected paper from CVPR’12). There is also criticism about how they don’t reflect the true functioning of what we know about the human brain. In the academic setting, another criticism I’ve noticed is how quite a few people suggest (I think, correctly) that “deep learning”, if just dealt with as a method for stacking ad-hoc layers and loss functions, is not worth a student’s time (see Ferenc Huszár’s views here). Another popular area of discussion which has recently gained importance is about how deep learning is essentially a black box which may be fine for prediction tasks where only the results matter, but not in inference problems or tasks requiring an explanation of its results.

Although all these comments on deep learning belong to very diverse areas and are often over-generalized (deep learning in practice isn’t a monolithic, standalone technique), in this post, I will write specifically about the notion of interpretability for these deep models. As the use of deep learning in real-life, decision-making systems increases, it becomes imperative that we are able to explain, to some degree, how our models come to the conclusions they do. But what exactly is interpretability and why is it needed at all? The remainder of this post discusses these two questions and finally explores some papers which try to make deep models more interpretable.

What is interpretability?

If a CNN model is to be made interpretable, what will make it so? Is it the features it generates, which should be interpretable, or the weights, or the choice of hyperparameters, or the learning algorithm, or the architecture itself? As far as supervised deep models are concerned, we know very well how the learning algorithm works to minimize the loss through gradient updates. We even have a fair idea of how the topology of these loss functions in the high dimensional space looks like and how we can possibly escape the local minima and saddle points and get to the optima. Does it mean that such a CNN model is interpretable? Or does knowing which specific neurons activate for an input and how the prediction accuracy varies when we obscure a part of the image make the model interpretable? Not necessarily. The questions above deal with various nuances of interpretability.

Zachary Lipton compiled his article on KDnuggets into a workshop paper called The Mythos of Model Interpretability at the 2016 ICML Workshop on Human Interpretability of Machine Learning. In section 3, he defines two characteristics of an interpretable model: Transparency and Post-hoc Interpretability, each with more sub-parts. Transparency, he defines as “opposite of blackbox-ness” and “some sense of understanding the mechanism by which the model works”, which seem like a very broad definition and highlights the difficulty in defining it. Post-hoc interpretability, on the other hand, is simply the extraction and analysis of information from models after they have been learned. Clearly, the first one is the more interesting characteristic here, but also the one more difficult to achieve. He also argues in these sections that the posterboy of model interpretability in machine learning, ie, a decision tree, can be analyzed simply because of its size and its computational requirements and that there is nothing intrinsically interpretable about them. He says this is the case for most techniques and that there is often a tradeoff between constraining the size of the model or its computational requirements and its performance which in turn is often a good reason to ignore the opaqueness of the model.

I personally think that the task of defining interpretability formally is not the best way to go about the problem of making models more interpretable. Answering the question ‘why interpretability’, on the other hand, can give more specific and useful ways to approach the problem.

Why do we need interpretability?

A very popular thought in the machine learning circle goes like this:

“The demand for complete interpretability from intelligent systems is overblown. Humans too are poor at explaining their decisions. We too are not completely interpretable.”

Although this statement glosses over a lot of specific legal, ethical and philosophical questions, it is important nevertheless to justify why or why not we need to invest time on transparent techniques which mostly will be transparent at the cost of performance. It helps to differentiate between the various motivations for such models.

1. Interpretability for real-world applications

This sentence from a blog is a good indicator of the need to have understandable models. “Try explaining an “ADAM Optimizer” to the judge when your GAN inadvertently crashes an autonomous vehicle into a crowd of innocent people.”

The reason why this is a good indicator isn’t because of its correct technical understanding of the GANs or the machine learning models deployed in a self-driving cars, but because of exactly the opposite reason. Users of these models are usually people who don’t understand these models. And they shouldn’t need to. Users should be able to trust these systems for them to adapted. It is interesting to note here that this motivation for interpretability is very different from the rest. The transparency that the model may provide might not serve any other purpose than to make the general public comfortable in using the system. This is in contrast to other motivations in the real-world where interpretability is largely a necessity. My first project in computer vision was to detect fire in industrial areas using surveillance cameras. The model consisted of a set of hand-engineered bag of features for the regions where motion was present followed by a binary classification using an SVM. I later discovered that it was not robust against adversarial video frames. A person walking past the camera with clothes of colours and textures similar to that of fire also triggered the system. But since the features were hand-engineered and small in number, I could identify why certain clothes predicted fire and subsequently managed to add more features like the flickering motion of fire pixels to handle the adversarial examples. On the other hand, deep CNNs have been known to be vulnerable to small, imperceptible adversarial changes in the input and don’t allow for a robust analyses for why this is the case, because, among other things, their distributed representations make it difficult to analyse how the neurons behave to adversarial examples. A lot of similar applications in healthcare and medicine also require justifications from the model as to why and how it produces its output. In fact this is one of the reasons why quite a few industries still use extremely simple linear models or decision trees. However, it is important to keep track of the implications of using/not using more complex models by compromising transparency and explainability. Some would argue that even if the inner functioning of an autonomous car is partially opaque, knowing from empirical experiments, just the fact that its adoption will reduce the the number of accidents and deaths is enough to give it a leeway in terms of the policy regulations. More generally, whether a use-case of machine learning needs to be interpretable, and if yes, then to what extent, must be decided on a case-by-case basis. This is something that was recently discussed at the panel discussion at the Frontiers of Machine Learning.

2. Interpretability for furthering research

Although many researchers don’t agree with this, the theoretical foundations of many practices in deep learning is lacking. The immense potential and the fast growth of the field has led the researchers to come up with a lot of practical techniques to train, improve and modify these networks, with the theoretical understanding of them lagging behind. One of the motivations to invest time in the interpretability of these models is to identify the limitations and make theoretically sound improvements to the existing models. The next section talks very briefly about some of the works that I know of which try to do the same.

Work in deep learning and interpretability

The papers mentioned here are deeply limited by my own reading list, so if I miss out on any important work, please let me know.

There has been a lot of work in trying to make deep models more explainable. For a clearer demarcation between these approaches, I find it useful to classify them into 3 types even though they aren’t necessarily mutually exclusive or exhaustive in nature:

-

Post-hoc interpretability

Most work done in explaining the predictions of neural networks belongs to this class of approach. It involves using a trained model and analysing the weights, features, co-occurrence patterns, sensitivity to obscuration and much more in order to understand what the network has learnt. Early work in vision often learnt a separate inverting mechanism to visualise features from already trained CNN models (see [1] and [2]). In the text domain, models trained using RNN/LSTM have also been analysed through post-hoc analysis of representations, predictions and errors of the model (see [3]) and [4]). Another popular work done in interpretability is LIME [5] which uses simpler surrogate models like linear models and decision trees to construct a model agnostic ‘explainer’. More recent works in vision like Excitation Backprop [6], Grad-CAM [7] and Network Dissection [8] try to obtain a visual explanation for the prediction through individual neurons and layers and then subject them to quantitative and qualitative experiments.

Post-hoc techniques are very useful in understanding the nature of features learnt and the predictions made, but are mostly empirical and qualitative. They explain the ‘what’ to some degree, but not the ‘how’. That being said, with post-hoc interpretability, models usually don’t have to sacrifice performance in order to be interpretable.

-

Inherent interpretability

The second class of interpretability approach is found in deep models where interpretability of some kind is achieved as a by-product of the model or the training method. The best example of this is the attention model. Networks trained with an attention module are inherently interpretable throughout training and at test time too. In tasks like captioning or visual question answering, attention over images and text allow us to visualise the parts of image and text the network is looking at in order to produce a prediction (see [9] and [10]). Similarly, attention in generative models like DRAW [11] allow a temporal visualisation of how the network generates an image. Another recent work in which the architecture allows for interpretability is the paper on visual reasoning [12], where the model itself contains functional modules and thus makes it possible to follow the chain of reasoning of the model. Apart from the architecture, the choice of objective which is optimised can also result in relatively more transparent models. For example, in [13], learning a MIL based detector on image regions using single-word concepts also leads to an attention-like visualisation of the image.

The obvious problem with this class of interpretable models is that they are very task-specific and thus can’t be extended to generic use-cases. Also, this kind of interpretability, like the first one, is also mostly limited to explaining the ‘what’ instead of the ‘how’.

-

Intrinsic interpretability

Instead of providing an account of the model which is extracted extrinsically, this class of approaches apply theoretical analysis to interpret what the models have learnt. The basic idea is that a better theoretical understanding of deep learning will yield models whose predictions and errors can be better explained. Lot of work done at Cambridge’s machine learning lab, previously by David Mackay’s group and now in Zoubin Ghahramani’s lab, have revealed bayesian interpretations of neural networks. More recently, Yarin Gal’s work [14] on how dropouts can be used for estimating uncertainty bounds on its predictions is one example where theoretical insights can enable us to quantify what the model does and doesn’t know (see slides from his talk).

In contrast to the previous class of models, this approach results in general explainability. Although there’s a lot of work done to explore how neural networks learn, they don’t necessarily translate to how they arrive at the predictions.

From my observations, the ‘black-boxness’ of deep learning is overhyped in some situations while in others it is underestimated. In the practical world, interpretability is needed only in specific circumstances and might serve a very different purpose than what research-world interpretability is expected to do. In any case, as we go forward, we will be seeing much more work on both these end-goals of having explainable models.

References

-

Understanding Deep Image Representations by Inverting Them ↩

-

“Why Should I Trust You?” Explaining the Predictions of Any Classifier ↩

-

Grad-CAM: Visual Explanations from Deep Networks via Gradient-based Localization ↩

-

Network Dissection: Quantifying Interpretability of Deep Visual Representations ↩

-

Show, Attend and Tell: Neural Image Caption Generation with Visual Attention ↩

-

Hierarchical Question-Image Co-Attention for Visual Question Answering ↩

-

Dropout as a Bayesian Approximation: Representing Model Uncertainty in Deep Learning ↩