Can Mechanistic Interpretability in Vision Foundation Models Support the Lofty Goals of Model Editing?

What is Mechanistic Interpretability (MI) and how is it different from previous interpretability approaches?

Mechanistic Interpretability (MI) seeks to understand internal mechanisms of how an ML model makes a certain prediction. Unlike previous interpretability methods like saliency maps, feature attributions, or probing classifiers, which try to relate the input to the output, the focus here is studying components of the model which are leading to the output.

Because MI aims to explain the inner workings of models in a structured and mechanistic way, it enables intervening on or editing the models towards a desired behavior while previous interpretability techniques are limited to simply post-hoc explaining the predictions.

Sparse Autoencoder (SAE) Models in MI

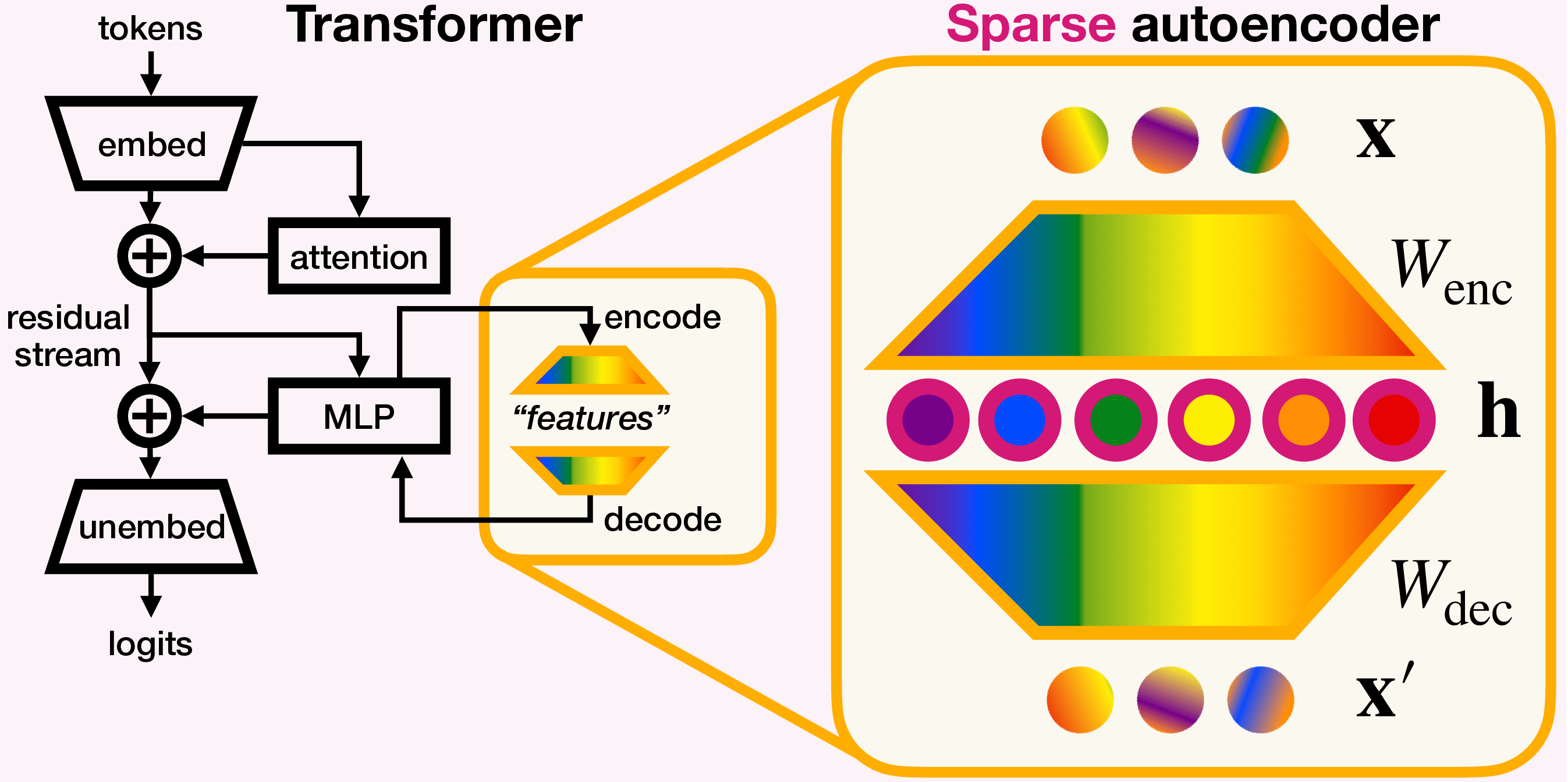

One of the key techniques used in the MI literature is the Sparse Autoencoder or SAE [1]. SAEs are designed to uncover latent, interpretable features within models by enforcing sparsity constraints during encoding (figure above; credits: [2]).

A big motivation behind SAEs is to disentangle model activations into a set of overcomplete, sparse, ideally monosemantic basis that correspond to human-understandable concepts. Variations of MI models exist beyond SAEs, such as direct circuit analysis or other unsupervised feature extraction techniques, but SAEs are among the most prominent tools used for mechanistic interpretability today.

In this discussion, I focus specifically on SAEs applied to Vision Foundation Model embeddings and their limitations when applied to model debugging and editing (which is already a known problem in LLM SAEs [3]). SAEs can be edited by enhancing, suppressing, clamping, or completely blocking the sparse unit responsible for a concept.

We’ve been experimenting with FM + SAEs recently in order to extract novel biological phenotypes from pathology images, but also to alleviate reliance on spurious confounders.

Why SAEs Fall Short for Model Editing

-

SAE Concept Spaces Differ from Human-Desired Interventions

The features learned by an SAE might not necessarily align with the conceptual abstractions that humans care about. This can be something fundamental or an artifact of SAE training.

When attempting to intervene on a particular model behavior—such as reducing harmful biases or guiding it away from known spurious confounders, the desired concept may not exist within the SAE’s overcomplete basis. This makes direct modifications challenging or even infeasible.

One example we recently saw was in trying to identify and block an SAE feature of our FM which corresponded to a spurious variable and was getting used partially to classify patient images. Even though the spurious variable is well-defined in the real world, we couldn’t find it expressed in the SAE features (no SAE unit correlated with it).

-

Sparsity Does Not Guarantee Interpretability

SAEs are built on the assumption that enforcing sparsity leads to interpretability. However, sparsity might be a necessary but insufficient condition.

A stream of work in unsupervised disentangled learning a few years ago is a reminder that sparsity can reduce the number of discrete features to analyze and has some good properties owing to information compression theories, but does not guarantee interpretable concepts.

Many sparse features may be statistical artifacts rather than meaningful decompositions of model behavior. Consequently, interventions based on these features may be unpredictable or ineffective.

-

Monosemantic Features Are Only Partially Monosemantic

While SAEs improve monosemanticity compared to raw foundation model activations, perfect disentanglement remains elusive. Features discovered by SAEs still exhibit some degree of entanglement, meaning that even if a feature strongly correlates with a concept, it is rarely exclusive to it.

This makes direct editing of individual SAE features an unreliable approach to controlling model behavior. We saw this firsthand where blocking the undesirable units led to a decrease in overall performance. Even if a concept existed in the SAE space, it could be fragmented into multiple units (feature splitting [4]). Similarly, multiple units sometimes expressed the same concept.

-

Lack of Concept Hierarchies and Relationships

SAEs capture isolated features but do not inherently encode relationships between concepts. Many real-world interventions require understanding how concepts are related—hierarchically or contextually.

There’s semantic structure in the real world which SAEs do not encode by design. For example, real-world concepts have:

- Hierarchy: (living things → animals → dogs → chihuahua)

- Relationships: (dogs are pets, have paws; cats have paws too)

- Compositions: (furry dogs, jumping animals)

SAEs lack explicit mechanisms for capturing these dependencies. Even though neural networks dislike forcing such handcrafted structure and inductive biases into model architecture, and I personally don’t believe it is the way to fix it, this limitation reduces the utility of current SAEs for editing. Some work around structured sparsity constraints might be one solution in this direction.

Can We Fix These Issues?

These issues require more deeper thought and I will add a follow up post on this, but here are some high-level ideas worth pursuing:

- Improving intervention techniques

- Linearity-based identification of monosemantic units is limiting, even with SAE features.

- We need to explore non-linear methods for introducing edits.

- Instead of modifying activations for one or more units, viewing the sparse codebook as a concept-space vector and the task of editing as finding a projection where undesirable concepts are minimally expressed is a better mental model.

- Introducing language-based editing

- I got interested in language-conditioned visual models because many of the complex visual concepts had lingual presence and manipulating or reasoning with discrete textual tokens was easier than pixels/objects space.

- Integrating text-based editing could offer better affordances.

- Connecting SAE spaces to textual concept spaces could allow one to steer the other.

- Building richer datasets for sparse dictionary learning evaluation

- SAEs learn codebooks in an unsupervised way, but we need stronger datasets with known discrete concepts for validation.

- LLMs could help construct a rich ontology for this.

- Defining and quantifying the coverage of SAE units across large-scale human-relevant concepts is crucial to avoid “Neural Pareidolia” (see a recent work on how SAEs learn interpretable units even with random parameters [5]).

- Exploring stacked SAEs or graph-based SAEs for hierarchical interpretability

- These could help build relational hierarchies.

- If combined with textual guidance, this could enforce structure more effectively than ad-hoc regularizers.

- Improving monosemantic constraints

- Vanilla SAEs do not enforce monosemanticity in their overcomplete basis.

- Adding penalties for feature splitting and redundancy might be necessary.

- Another objective beyond reconstruction and sparsity may help enforce monosemantic behavior even though these penalties can feel like patch-work.

- Incorporating information about what edit directions are needed

- The challenge of feature splitting/absorption highlights a fundamental issue familiar to representation learning and cognitive science circles: Concepts are contextually activated and difficult to decompose without specifying the right abstraction level or context.

- A promising research direction is making SAE latents editable in a context-aware manner. If we can define the direction for edits in feature space, could we achieve more effective SAE training?

- For example, in medical imaging, if we know that certain variables such as tissue source or scanner type are confounders, could we integrate this information directly into SAE training? Doing so could enhance the interpretability and controllability of interventions.

References

-

Towards Monosemanticity: Decomposing Language Models With Dictionary Learning ↩

-

Towards Principled Evaluations of Sparse Autoencoders for Interpretability and Control ↩

-

A is for Absorption: Studying Feature Splitting and Absorption in Sparse Autoencoders ↩

-

Sparse Autoencoders Can Interpret Randomly Initialized Transformers ↩